Purpose and the dangers of ignoring basic principles.

It was only two weeks’ ago that we shared our thoughts on how to define a corporate purpose (and almost four years since our first blog on the topic). Purpose has been in the news almost daily since and this, combined with a number of global brands announcing their own statements of ‘purpose’ (and in our view making some basic errors) has compelled us to write again to warn of the pit falls.

But first, why has purpose become such a hot topic? On Radio 4 this week Professor Colin Mayer of Oxford Said business school gave an informed view on the current lack of public trust in large corporations. He spoke of big companies having lost their direction, that previously (in the years after the industrial revolution) businesses had always had a public role; a purposeful meaning, but as businesses became national, then international and then global, their attachment, engagement and support of communities diminished to the point where almost all big businesses today are totally detached from society. And in an avowedly unequal society capitalism is being challenged – profits before planet, CEO pay ratios, London-centricity, corporate tax avoidance etc – as a faulty model. Today, as businesses grapple with how to restore trust, many are looking to use a statement of purpose to reconnect business with society.

There are some great historical examples of companies that got ‘purpose’ right, such as the chocolate companies started by the Quaker families. We’ve written previously of how these companies supported workers and played a huge role in establishing workers’ rights still enjoyed today. What’s fascinating (in the context of purpose) is that these companies were started with a clear social purpose from the outset. At the time, many English households started the day with a pint of Ale for breakfast (seriously!) meaning large swathes of the workforce were drunk before even arriving at work. The Quakers recognised this was unhealthy, unproductive and (believed it) ungodly so set about changing that behaviour by encouraging people to start the day with a cup of hot chocolate. This was business strategy with social purpose – business and purpose in perfect harmony. It set up a virtuous circle whereby employees benefited and were more productive, thus the business became more profitable and grew, thus generating more jobs and a healthier workforce. This was making a commercial opportunity out of a social need – a true and clear purpose. And it worked because it was authentic.

The problem with how purpose is being developed and defined today, is that it’s mostly being done retrospectively. This in itself isn’t necessarily a problem, but it does run the risk of grand statements of purpose being developed in isolation, detached from business reality and/or the corporate brand positioning and therefore lacking authenticity. It can feel like something imposed, or retro-fitted, the very opposite of the sense of a purpose that drove the business in the first place. The danger here is that these companies will be viewed cynically as ‘worthy washing’ i.e. virtue signalling without genuine intent, action and impact.

One consequence of this rush to find a purpose is that corporate leaders get sent out into the media jungle with a set of words and aspirations which they themselves do not necessarily feel in their hearts. The moment they are expected to extemporise on the theme when under the studio lights the thin veneer begins to melt. We heard the boss of a newly rebranded bank announce on a high-profile news programme recently that this rebranding was a recognition of where the bank is today as a purpose led business. There followed some reference to this not affecting customers – probably intended to be reassuring but actually having the effect of confusing: Surely, if a business is to be purpose led, then customers are the primary audience that should be affected by said purpose? And if customers aren’t to benefit from a company becoming a purpose-led business with a new name, then who will? We’d like to think it could be employees or society at large, but that wasn’t in the script. At least we would like to have seen a more honest narrative about why there was a need for a change and what was behind it – something credible about how the new branding was a better reflection of where the business is today and what it stands for.

Nike’s new purpose statement tells us that “NIKE’s purpose is to unite the world through sport to create a healthy planet, active communities and an equal playing field for all. These are more than aspirations – they are foundational priorities that shape decisions across every aspect of our business.” This all sounds very lofty and worthy but is it credible? Exactly how is Nike going to ‘unite the world’? How will be know when Nike has created a ‘healthy planet’? Do we even believe these things can be achieved by a profit-making company? Do customers even care?

We feel that a huge issue with the above statement is that it actually detracts from what should be a fantastic brand story. First, Nike’s original mission statement is to “bring inspiration and innovation to every athlete in the world”. Which (for us) sounds more credible and relevant than its statement of purpose. (Arguably – and controversially perhaps – that was its original purpose). But more importantly, Nike has an authentic brand story. Nike became a ‘cool’, aspirational brand because in the late 70’s and early 80’s it became the brand of choice for urban black kids. They made it cool. They were Nike’s original cult following. Surely if Nike reconnected its brand story with this truth that would do more good than a wooly statement to ‘unite the world’? As is often the case, the truth is usually the better story. And as we know in the brand world, authenticity is everything.

Finally, to Coca Cola. According to reports, Coca-Cola is investing in a huge purpose-driven marketing campaign across Western Europe that seeks to position the drink as one that “unites people” in what it sees as an “increasingly divided and hostile world”. This echoes its ground-breaking 1971 “I’d like to teach the world to sing” advertising. The difference is that back then it didn’t feel the need to explain itself in rational terms in the way it seems to now. So, Coca Cola is joining Nike in its purpose to ‘unite the world’ but again not telling us how it intends to do this or why it thinks it will succeed where the UN has (seemingly) failed. What’s jarring about this purpose statement from Coca Cola is it misses a trick in not going back to the sentiment behind what it was saying in 1971. Today Coca Cola feels the need to cloak its proposition in corporate purpose-speak. So rather than giving us an implied message through beautifully crafted advertising that leaves us with a warm glow of togetherness, what we’re given is an explicit statement that can easily be dismissed as more big brand worthy washing.

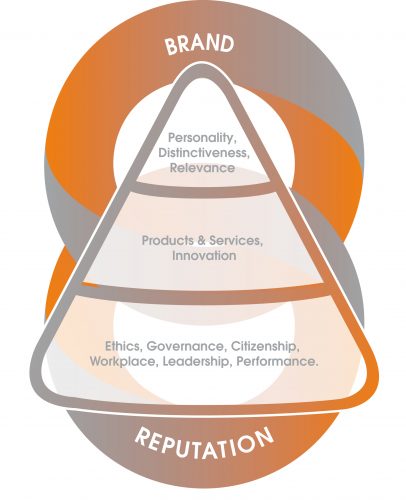

As we’ve always said, it’s no bad thing when companies seek to be purpose driven, but any statement of purpose must reflect the business reality – it must support the company’s brand(s), the corporate reputation and the commercial strategy. Above all, it must be authentic. Anything else is just tinkering around the edges.